製造業での成功は物理的なものにかかっている。最高のものを作るには、最高の設備で最高の部品を最高の効率で組み立てる。サービス業での成功は、人にある。適切な人を雇い、適切にモチベーションを持たせる。製造業が科学に似ているなら、サービス業はアートに似ている。

人にモチベーションを与えるのはかなり複雑だ: ウィジェットはいつ使われるか知らない。従業員は同僚とコネクションを作る。ソーシャルな理由かもしれないし、仕事上の理由かもしれない。マネージャーが予想しなかった理由かもしれない。

Yale School of Managementで組織行動について教鞭を執るMarissa Kingは、こうしたネットワークについて研究している。彼女は、最近の著書”Social Chemistry: Decoding The Elements of Human Connection”でネットワークの分類を試みている。

「ネットワーキング」という言葉を聞くと、よくないイメージが浮かぶ人も多いだろう。上司にこびいり、同僚は昇進を優先して助け合いをせず、無視しあう人間が頭に浮かぶ。Kingは、プロフェッショナルな関係性を戦略的に考えることについて、3分の2の教授が同意しがたいか、完全に意見を異にする研究を引用している。

生産性の観点から、もっとも大事なネットワークは、社内の異なる所属の従業員によって作られるネットワークだ。多様な視点はより大きなクリエイティビティにつながる。これは会社にとってのみならず、働くものにとってもよいことだ。研究によれば、異なる部門の同僚に追いつこうとすることが、給与の増加や従業員の満足度とつながっていた。

従業員の中には、このような協力関係を仕切りのないオフィスにすることで促進しようと考えたものもいた。しかし、研究によれば、伝統的な部屋ごとに仕切られたオフィスにくらべ、仕切りのないオープンなオフィスは、生産性、クリエイティビティ、モチベーションを下げるという。社員同士の交流において、大事なのは量より質なのだ。パンデミックによって多くの人々が自宅で作業しており、パンデミックは多くの協力的なコミュニケーションをだめにしたかもしれない。

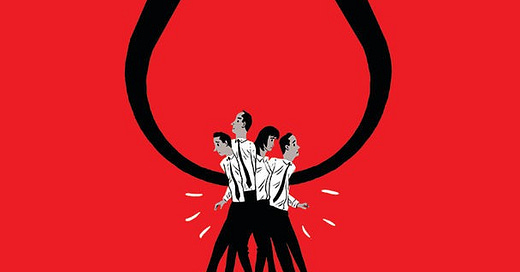

Kingによれば、人々は3種類のネットワークを築きがちだ。”拡大”は広く浅い関係、”招集”は狭く深い関係、”仲介”は異なるネットワークの人々をつなぐ関係だ。

表面的には、これらの分類は納得がいくものだが、果たして役に立つものなのだろうか。読者はオンラインテスト (www.assessyournetwork.com) でどのカテゴリーに自分が該当するのかわかる。Bartleby (訳注: おそらくTHE ECONOMISTの本記事のライター) はテストを受けたのだが、彼が予想していた通り、どれにも該当しなかった。実際、著者によると、3分の1の人々はどれにも該当せず、20-25%の人々はミックスだと判定される。言い換えると、半分以上の人をカテゴライズすることができないのだ。

さらに混乱させることに、Kingはサブカテゴリーも用意している。協力的な仲介、さやとり仲介、拷問されたブローカーなどだ。人によっては、あるカテゴリーから別のカテゴリーに遷移する者もいる。現時点では、北イングランドのふるい言葉を借りて、このように受け止めるしかない。”there’s nowt so queer as folk.” (人間ほど不思議なものはない)。幸いなことに、Kingの著書”Social Chemistry: Decoding The Elements of Human Connection”は多くの知識やおもしろい逸話に満ちており、単なる科学的な分類ではなく、もっとインサイトに満ちたものだ。

以下に述べる2つの研究は共通の問題を示している。人はとても狭い関心を持ってしまう傾向にあるという問題だ。ある実験では、4人に1人のスマホユーザーしか、画面を見ているとき、目の前を一輪車に乗ったピエロが通っても気がつかなかった。また、カトリック教会のセミナーでは、講演者は「善きサマリア人」を読みながら、苦しむ参加者の隣を通り過ぎた。正しいネットワークでは、参加者に多様性があれば、もっと大きく物事をとらえることができるのかもしれない。

礼儀といった昔ながらのものも役に立つとKingは言う。笑顔のような単純なジェスチャーや、「ありがとう」と言うだけでも、同僚には好かれやすいし、より協力的な関係を築ける。対照的に、職場で無礼な扱いを受けた従業員に関する研究は、従業員の職場での努力や勤務時間やコミットメントがすべて減ったことを報告している。Kingの指摘は、次のような格言を思い出させる。誰かが「くそやろう」かどうかは、自分より地位の低い人をどのように扱うか観察することでわかるという格言だ。「くそやろうになるな」は科学的な命題ではない。しかし、今でもマネジメントにおけるかなりよいモットーなのだ。

感想

ビジネスモデルにおけるネットワーク効果についての記事かと思って読んだのですが、全然違った内容でした。また、お詫びですが、第2パラグラフ (ウィジェットは…) の原文の意味がはっきりせず、訳がおかしいかもしれません。

原文

SUCCESS IN MANUFACTURING depends on physical things: creating the best product using the best equipment with components assembled in the most efficient way. Success in the service economy is dependent on the human element: picking the right staff members and motivating them correctly. If manufacturing is akin to science, then services are more like the arts.

Motivating people has an extra complexity. Widgets do not know when they are being manipulated. Employees also make connections with their colleagues, for social or work reasons, that the management might not have anticipated.

Marissa King is professor of organisational behaviour at the Yale School of Management, where she tries to make sense of these networks. She attempts a classification in her new book, “Social Chemistry: Decoding The Elements of Human Connection”.

The term “networking” has developed unfortunate connotations, suggesting the kind of person who sucks up to senior staff and ignores colleagues who are unlikely to help them win promotion. Ms King cites a study which found that two-thirds of professionals were ambivalent about, or completely resistant to, thinking strategically about their professional relationships.

From the point of view of productivity, the most important networks are those formed by employees from different parts of the company. Diverse viewpoints should lead to greater creativity. They are good for workers, too. A study found that catching up with colleagues in different departments was linked to salary growth and employee satisfaction.

Some employers had the bright idea of encouraging this co-operation by moving to open-plan offices. But research suggests that workers in open-plan layouts are less productive, less creative and less motivated than those in offices with a traditional, room-based design. The quality of interactions is more important than the quantity. The pandemic, by forcing many people to toil away at home, has probably corroded some of these co-operative arrangements.

Ms King says that people tend to construct three types of network. “Expansionists” have a wide set of contacts but their relationships tend to be shallow. “Conveners” have a small number of relationships but these are more intense. “Brokers” link people from different network types.

On the surface, this categorisation seems reasonable. How useful is it? Readers can take an online test (at assessyournetwork.com) to see which category they fall into. Bartleby did so and found (as he expected) that he did not fit into any of them. Indeed, the author’s research shows that one in three people does not have a clearly defined style and 20-25% could be classed as mixed (for example, they are simultaneously brokers and expansionists). In other words, more than half of people cannot be neatly categorised.

To add to the muddle, Ms King introduces sub-categories: co-operative brokers, arbitraging brokers, tortured brokers, and so on. Some people move from one category to another (like a certain Heidi Roizen, who, in a feat of management jargon, “transitioned from an expansionist to a broker to a convening nucleus”). At this point it seems wiser to admit that, to use an old phrase from the north of England, “there’s nowt so queer as folk”. Fortunately, the book is full of wisdom and entertaining anecdotes which show that stories can be more insightful than attempts at scientific categorisation.

Two fun studies outline a common problem—the tendency for people to have too narrow a focus. In one test, only one in four mobile-phone users noticed a clown who unicycled past them while they were looking at their screens. In another revealing story, Catholic seminarians strode past a distressed bystander while in a hurry to give a lecture on the parable “The Good Samaritan”. In the right network, the presence of a diverse set of participants may allow the group to see the bigger picture.

Old-fashioned concepts like courtesy can also help, Ms King argues. Simple gestures—a smile, a “thank you”—make colleagues more likeable and increase co-operation. In contrast, studies of workers who experience incivility find that their effort, time spent at work and commitment to the job all reduce. Ms King invokes the aphorism that “assholes” can be identified by observing how they treat people with less power. “Don’t be an asshole” is not a scientific statement. But it is still a pretty good management motto.

この「ウィジェット」はプログラムという意味合いで使われているみたいですね

つまり人間に内蔵されているプログラム群みたいな意味での「Widgets」と解すると、その後の文も繋がると思います

オフィスマネジメントもリモート中心になると新たな問題が出ているように感じますね

個別のオンライン会合でより気軽に会社や上司や同僚の悪口合戦ができるので・・・🧐